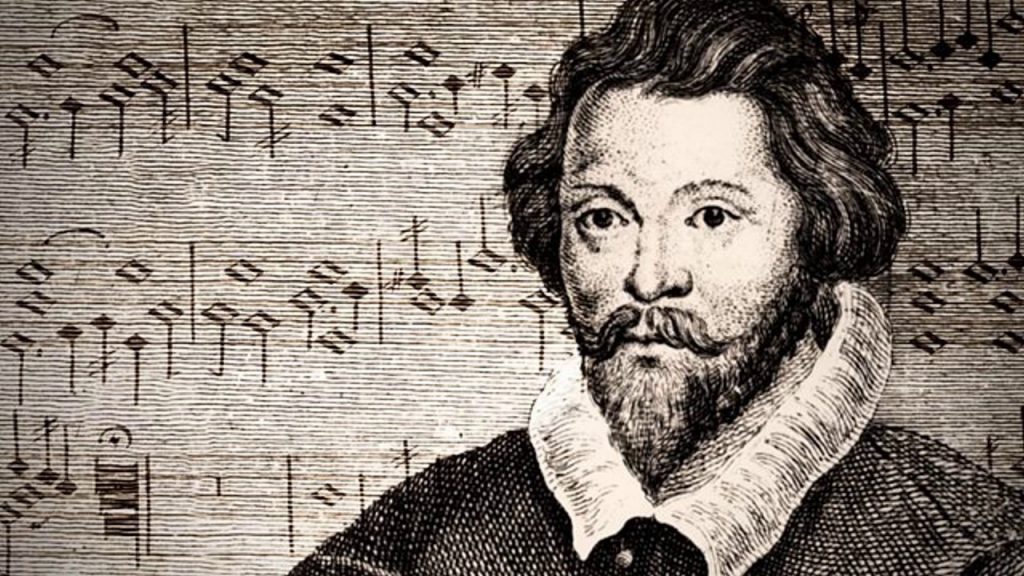

Alessandro Striggio (circa 1536/1537 – February 29, 1592), an Italian composer, instrumentalist and diplomat of the Renaissance was born in Mantua, likely into an aristocratic family. Although specific details regarding his early life are limited, it is generally believed that he relocated to Florence during his formative years. On March 1, 1559, he started his professional employment with Cosimo de’ Medici as a composer and musician. In 1567, the Medici entrusted him with a diplomatic mission to England, during which it is reputed that he had the opportunity to meet Queen Elizabeth I and Thomas Tallis. Throughout the 1560s, Striggio composed numerous works for the Medici family, including the renowned 40-voice motet “Ecce beatam lucem an ancient, celestial melody woven into a Pindaric ode penned by the passionate and fervent neo-Latin poet, Calvinist Paul Schede Melissus (1539–1602)..

Ecce beatam lucem;

Ecce bonum sempiternum,

Vos turba electa celebrate Jehovam eiusque natum

aequalem Patri deitatis splendorem.

Virtus Alma et maiestas passim cernenda adest.

Quantum decoris illustri in sole,

quam venusta es luna,

quam multo clar’honore sidera fulgent, quam pulcra quaeque in orbe.

O quam perennis esca tam sanctas mentes pascit!

praesto gratia et amor, praesta nec novum;

praesto est fons perpes vitae.

Hic Patriarchae cum Prophetis, hic David,

Rex David ille vates,

cantans sonans adhuc aeternum Deum.

O mel et dulce nectar, O fortunatam sedem!

Haec voluptas, haec quies, haec meta, hic scopus

Nos hinc attrahunt recta in paradisum.

Behold the blessed light,

behold eternal goodness,

You throng of the elect, praise God and His Son

who is equal to the Father; praise the splendour of the deity.

Benign power and majesty are seen everywhere.

The dazzling splendour of the sun

is matched by you, the moon,

and by the stars shining brightly in their great glory.

O how such eternal nourishment feeds holy minds!

Mercy and love are here, and always have been;

here is the eternal fount of life.

Here the Patriarchs and Prophets, here David,

King David the bard,

singing and playing instruments still praise eternal God.

O honey and sweet nectar, O blessed place!

This delight, this peace, this goal, this mark

draw us from here straight to Paradise.

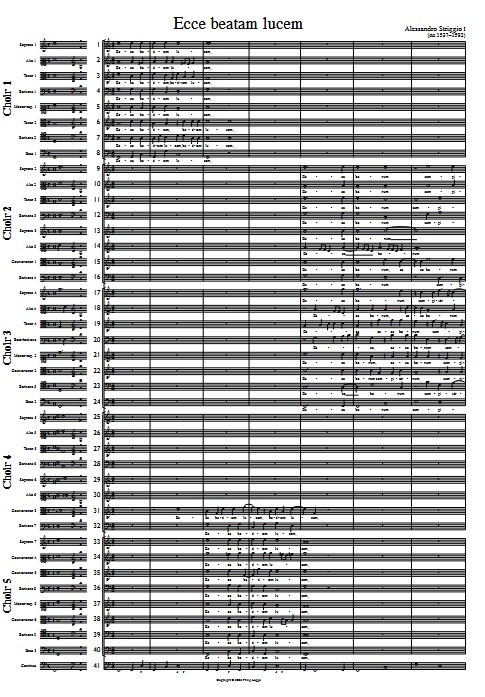

Alessandro Striggio’s breathtaking masterpiece, the forty-part motet Ecce beatam lucem, a timeless celestial harmony embedded within a Pindaric ode composed by the passionate and dedicated Neo-Latin poet, Calvinist Paul Schede Melissus (1539–1602), endures as a divine testament to the divine artistry of the human spirit! Its words, first unleashed upon the world in the fiery year of 1595, carried the soul of something infinitely profound—an ancient, celestial melody woven into a Pindaric ode penned by the passionate and fervent neo-Latin poet, Calvinist Paul Schede Melissus (1539–1602). This celestial symphony of forty voices, woven together with such profound passion and luminous grace, is preserved in a singular, irreplaceable manuscript—a precious relic etched in history’s vaults, dating back to the awe-inspiring year of 1587. And where does this priceless treasure reside? It rests within the sacred walls of the Ratsschulbibliothek, Germany.

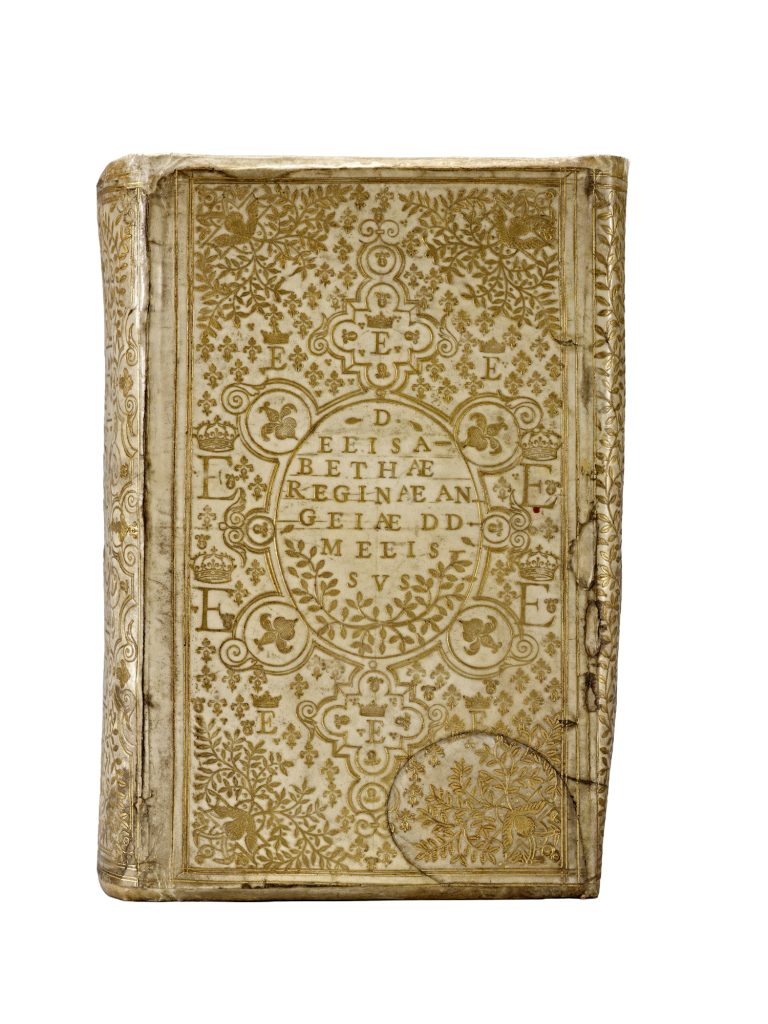

Paul Melissus, one of the most radiant stars in the constellation of sixteenth-century Europe’s poets! Oh, how the very words shimmer with the fervor of a thousand passionate hearts, for Melissus, beloved poet laureate of the Holy Roman Empire, ventured across tumultuous seas and treacherous lands in 1585, driven by a desperate, soul-consuming desire to escape the chains of religious persecution that threatened to crush him in France after the cruel Treaty of Nemours.

Imagine the thunderous emotion that must have surged within him as he stepped into the opulent halls of the English court, a land he hoped would embrace his talent and renew his spirit with royal favor! In a blaze of poetic fervor, he poured forth all he had—his collected poems—dedicated to Elizabeth with trembling hope, beseeching her benevolent patronage, longing for the golden touch of her grace to ignite his suffering soul.

Yet, amid the echoes of passionate verses addressed directly to the queen—who herself once responded with a heartfelt poem—Melissus found disappointment’s bitter taste, for his plea was unanswered and his hopes dashed like fragile glass. In the end, he departed from England in 1586, unable to bear the ache of unrequited devotion, seeking solace and new purpose as a librarian and counselor in Heidelberg. Oh, the poignant tragedy of a poet’s fervent love for a sovereign who, despite her own poetic exchanges with him, could not reciprocate his ardent longing!

Ecce Beatam Lucem words, first unleashed upon the world in the fiery year of 1595, carried the soul of something infinitely profound—an ancient, celestial melody woven into a Pindaric ode penned by the passionate and fervent neo-Latin poet, Calvinist Paul Schede Melissus (1539–1602). It is a vision born from the heart of a radical, an almost unearthly glimpse of the New Jerusalem, bursting with the radiant hope and relentless passion of a Calvinist soul yearning for eternity. It was perhaps whispered into existence as a contrafactum—an altered song—for an unnamed, secret occasion—a mysterious event. It is a clandestine spark of divine inspiration, shrouded in enigma and charged with a fervor that defies all boundaries, forever echoing the restless, fiery spirit that drove its creation, a testament to the transcendent power of music to unite, elevate, and inspire!

Dr. William Barton of the Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for Neo-Latin Studies in Innsbruck offers a valuable scholarly insight into the phrase “ver novum” within Melissus’ poem. It has come to our attention that all existing recordings and concert programmes contain a significant textual error that bears on the interpretation of the piece. Specifically, the fourth line of the first verse should read “Praesto ver novum” (“Here is a new spring”), rather than “Praesto nec novum”—which has been variously translated as “Here and not new,” “and always have been,” or “as they always have been.” The corrected text reflects an anticipation of something new and forthcoming, rather than referencing something from the past.

https://www.hyperion-records.co.uk/dw.asp?dc=W21247_GBLLH1956001

The CD booklet of Ecce Beatam Lucem released by Hyperion Records in May 2019 has the following notes;

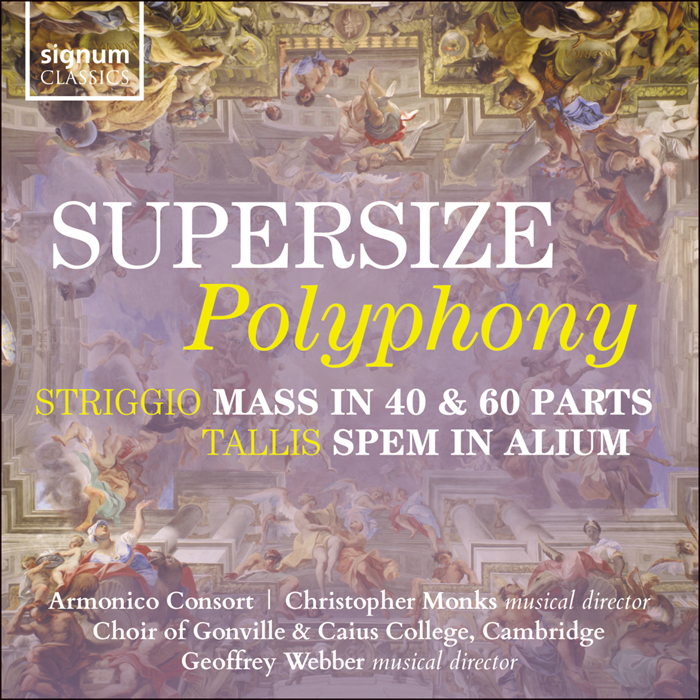

In 1561, Striggio composed the renowned forty-part motet, Ecce beatam lucem a historic celestial composition integrated into a Pindaric ode authored by the dedicated and enthusiastic Neo-Latin poet, Calvinist Paul Schede Melissus (1539–1602) and subsequently embarked on a European tour with the work—reportedly transporting all forty part-books attached to a donkey. During his travels, Striggio visited England, where it is believed he met Thomas Tallis, who would have likely been familiar with this significant composition. It is commonly hypothesised that Tallis drew inspiration from this motet for his own forty-part work, Spem in alium, as suggested by a note from a law student.

‘In Queene Elizabeths time there was a songe sent into England of 30 parts (whence the Italians obteyned the name to be called the Apices of the world) which beeinge songe mad(e) a heavenly Harmony. The Duke of ‘_____’ bearing a great love to Musicke asked whether none of our English men could sett as good a songe, & Tallice beinge very skillfull was felt to try whether he would undertake the Matter, which he did and mad(e) one of 40 p(ar)ts which was songe in the longe gallery’ at Arundell House.’

It is likely that the elusive ‘Duke’ referred to is the Duke of Norfolk, who is thought to have commissioned Spem in alium as a challenge to English composers to produce music finer than that of their Italian counterparts. Indeed, the piece was first performed at Arundel Castle, as described. The mention of thirty parts seems to be a misunderstanding of Striggio’s forty-part work, but the reference to ‘heavenly harmony’ is something which is highly-significant even today. The listener’s overall response to these compositions, particularly when centrally positioned within the soundscape, is profoundly engaging: it offers a harmonically rich experience that is both distinctive and exceptional.