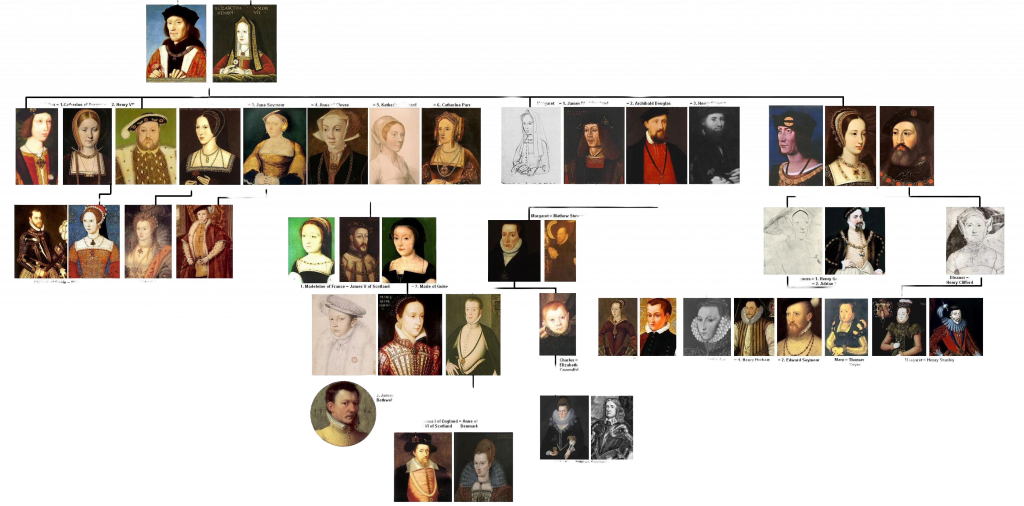

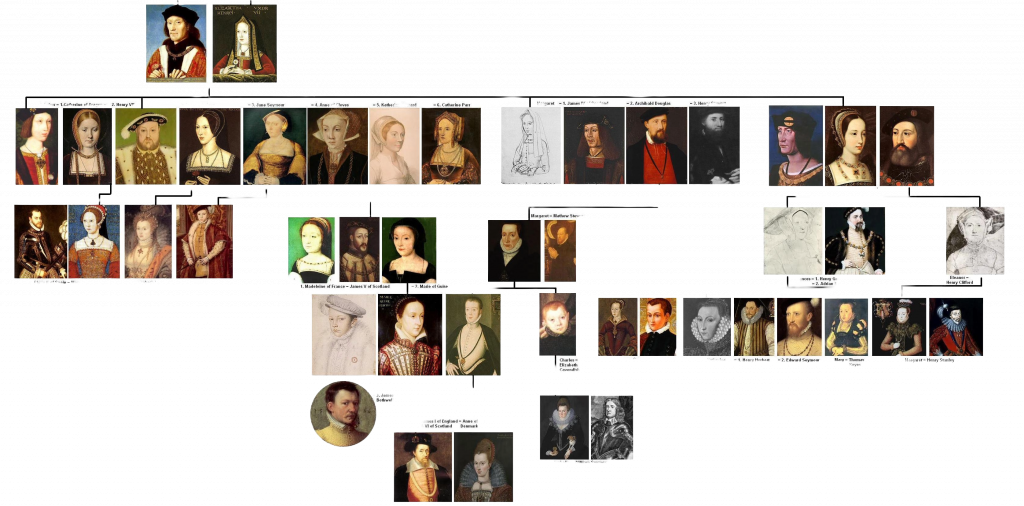

The English Reformation was a pivotal period of religious transformation during the Tudor era, characterised by a series of significant shifts in church doctrine and governance. It commenced with King Henry VIII’s (28 June 1491 – 28 January 1547) decision to sever ties with the Roman Catholic Church in order to obtain the annulment of his marriage of Catherine of Aragon (16 December 1485 – 7 January 1536). In 1534, he convened Parliament to enact the Act of Supremacy, which declared the monarch as the Supreme Head of the Church of England, formally establishing independence from papal authority.

Henry VIII enacted multiple legislative measures to determine the succession to the throne upon his passing.

In 1534, the first Act of Succession was established, mandating that subjects acknowledge King Henry VIII’s marriage to his second wife, Anne Boleyn, as lawful and sincere. Anne Boleyn, to be the heir to the throne, with any boys would take precedent over girls. Anne’s first child was Elizabeth which made her heir to the throne unless Anne gave Henry what he ultimately desired – a boy.

Another part of the Act required all subjects to swear an oath to recognise Anne as his legal wife and any children they have the true heirs. It also demanded that Henry’s subjects recognise him as the head of the church. Anyone not swearing the oath was arrested under the Treasons Act. Some notable subjects that refused to take the oath included Sir Thomas More and Bishop John Fisher both were later executed for treason.

The Second Act of Succession of 1536 resulted in the removal of both Elizabeth, Henry VIII’s daughter with Anne Boleyn, and Mary, his daughter with Catherine of Aragon, from the line of succession when he married Jane Seymour. At the time of the enactment of this legislation, Henry VIII had declared all of his children to be illegitimate, thereby disqualifying them from succeeding him. This act paved the way that his son Edward with Jane Seymour was to be heir to the throne.

This status was later revised following the birth of Edward in 1537, the son of Henry VIII and his third wife, Jane Seymour. Towards the conclusion of Henry VIII’s reign, he enacted the Third Succession Act in 1543, which revised the royal succession to place his daughters, Mary and Elizabeth, behind their younger half-brother, Edward, thereby formalising their positions within the line of succession.

Henry VIII’s successor, Edward VI (12 October 1537 – 6 July 1553), continued the advanced Protestant principles through comprehensive ecclesiastical reforms.

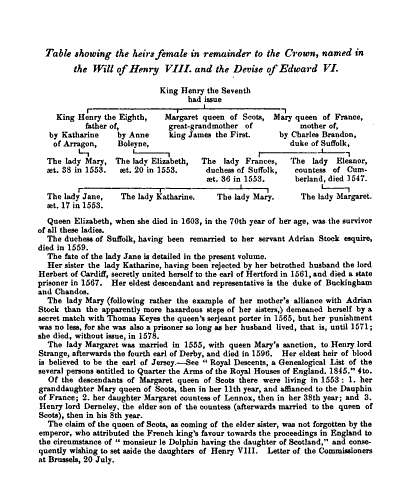

Henry VIII made a final revision to his last will and testament on 30 December 1546. It confirmed the line of succession as one living male and six living females.

- Mary

- Elizabeth

- Jane

- Katherine

- Margaret

The will containing the line of succession was read, stamped and sealed on 30 December and placed in the custody of Edward Seymour, Earl of Hertford. After Henry died on the night of 27-28 January 1547, the will was locked in a box to which only Hertford had the key, delaying its reading to Parliament by Henry’s principal secretary until Hertford returned the key after he had secured the person of Prince Edward, Henry’s son and heir. The document is still extant, but this fact was not generally known or accepted by the 1560s, when some believed it was lost, or had been destroyed.[4

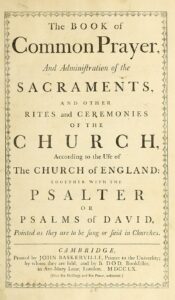

During Edward VI’s reign, Parliament enacted additional legislation, including the Act of Uniformity 1549, which established the Book of Common Prayer as the standard liturgical text, thereby solidifying Protestant practices within the Church of England, emphasising doctrinal change. Under the guidance of prominent reformers such as Archbishop Thomas Cranmer, the Church of England integrated more explicitly Protestant doctrines, resulting in revisions to liturgy and church practices to reflect Protestant principles.

Following the death of King Henry VIII, Edward VI ascended to the throne. At the time of his accession, Edward was only nine years old and experienced frequent health issues. His reign was characterised by significant influence from noble factions seeking to advance their own interests. John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland (1504– 22 August 1553) was an English military officer and politician, who led the government of the young King Edward VI from 1550 until 1553, and unsuccessfully tried to install Lady Jane Grey (1536/1537 – 12 February 1554) as Queen.

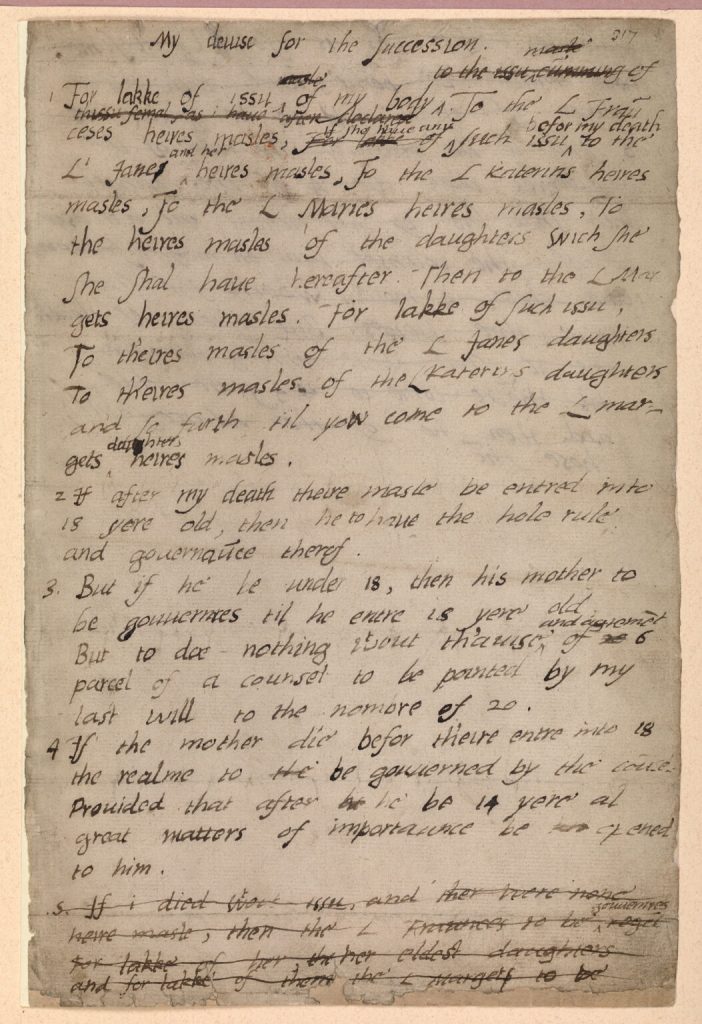

This decision circumvented the established line of succession, which designated Mary as the rightful heir under the 1543 Act. Lady Jane Grey, as a great-niece of Henry VIII, had a legitimate claim to the throne, although she was lower in the line compared to Mary and Elizabeth.Edward VI’s “Devise for the Succession” was a formal document drafted to alter the line of inheritance by disinheriting his Catholic half-sisters, Mary and Elizabeth, and designating his Protestant first cousin, Lady Jane Grey, as his heir. Although this “Devise,” issued in June 1553, was not formally approved by Parliament and thus did not constitute a legally binding act, it reflected his intention to ensure a Protestant successor and support Edward, a committed Protestant, who aimed to prevent his half-sisters from reversing the religious reforms established by his father and himself. The devise was subsequently amended to specify that the throne would pass to Jane and her male heirs. Jane’s brief nine day “reign” concluded when Mary successfully garnered support and ascended to the throne; ultimately, Elizabeth succeeded Mary and reestablished Protestantism as the dominant faith in England.

While the “Devise” ultimately did not succeed in establishing Jane as queen, it influenced future succession policies. Edward’s efforts contributed to the eventual ascension of Elizabeth I, who solidified Protestantism in England. As the devise was neither ratified by Parliament nor legally enacted, it did not supersede existing legislation such as the Act of Succession established by Henry VIII. Following Edward’s death on 6 July 1553, Jane was proclaimed queen, but her “reign” was very short-lived—lasting only nine days—before Mary consolidated support and claimed the throne. Lady Jane Grey was executed for treason 12th February 1554 at the Tower of London.

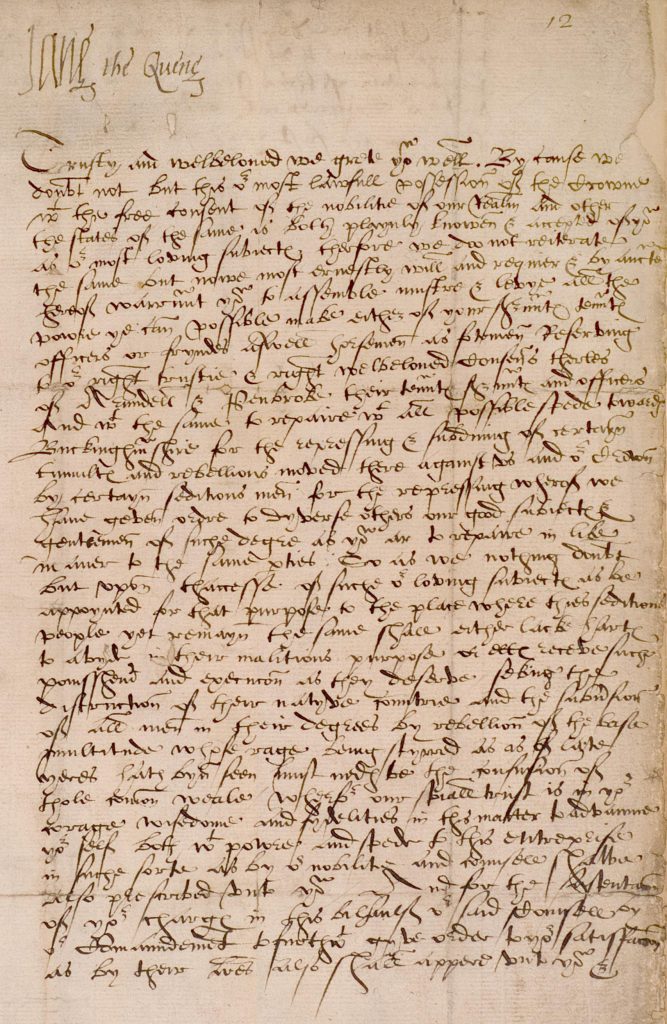

Lady Jane Grey wrote at least two significant letters during her brief tenure as monarch: a formal letter addressed to the Sheriff, Justices, and Gentlemen of Surrey advocating for the recognition of her legitimate claim to the throne and discouraging support for Queen Mary; and a farewell message delivered on the scaffold before her execution, wherein she reflected on her sins and petitioned for divine mercy. An additional letter, written to Queen Mary after her deposition, is also documented.

Letter to the Sheriff, Justices, and Gentlemen of Surrey (July 16, 1553):

This communication, issued under Queen Jane’s official signet, encourages their loyalty by asserting that King Edward VI’s will designated her as successor and cautions them against accepting any correspondence from Queen Mary. Its primary purpose was to garner support for her claim and to mitigate potential unrest within the region. This letter is preserved within historical collections, such as the Exploring Surrey’s Past archive.

Letter to Queen Mary I (post-November 10, 1553):

In this letter, Lady Jane Grey describes the circumstances surrounding her brief reign and expresses her reluctance to assume the crown. She states that she did not seek the throne but was persuaded to accept it to prevent a Catholic succession, asserting that her consent was obtained under duress. The correspondence serves to affirm her innocence and her commitment to her principles.

Farewell Statement on the Scaffold (February 12, 1554):

Ahead of her execution, Lady Jane Grey delivered a brief, multilingual farewell speech in Latin, Greek, and English. In it, she acknowledged the justice of her condemnation but expressed confidence that her soul would receive divine mercy for her sins. She also reflected that her death was a transformation for the better, leading her to eternal life rather than earthly existence.

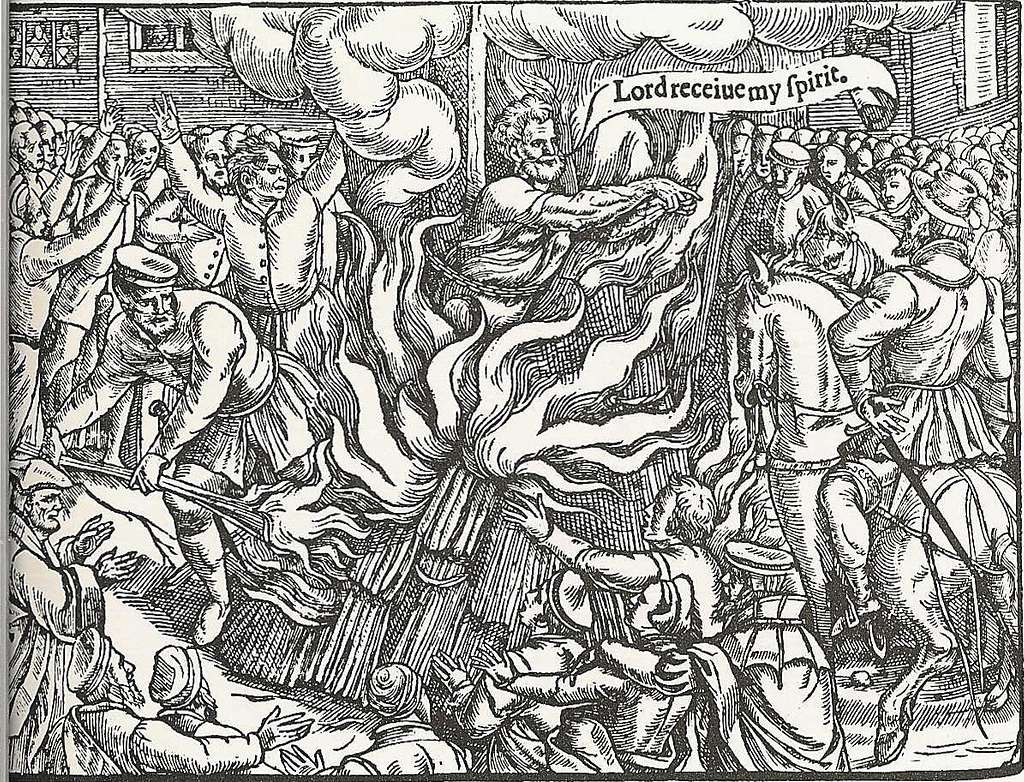

Over her five-year tenure, her government conducted the Marian persecutions, which resulted in the execution of over 280 individuals convicted of religious dissent, a period often referred to as the era of her nickname, “Bloody Mary.”

n; however, she was later reinstated in the line of succession by the Third Succession Act of 1543. Her younger half-brother, Edward VI, succeeded Henry VIII in 1547 at the age of nine. In 1553, with Edward approaching the end of his life, he sought to exclude Mary from the succession due to her Catholic faith and her intention to reverse Protestant reforms. Consequently, a group of leading political figures proclaimed Lady Jane Grey as queen. Mary swiftly responded by raising forces in East Anglia and successfully deposed Lady Jane Grey to become queen.Mary I (18 February 1516 – 17 November 1558), also known as Mary Tudor, served as Queen of England and Ireland from July 1553 and was also Queen of Spain through her marriage to King Philip II from January 1556 until her death in 1558. During her reign, she actively sought to restore the Roman Catholic Church and reverse the religious reforms initiated during her father, King Henry VIII’s, rule. Her efforts to regain church property confiscated in previous reigns faced significant opposition from Parliament. Over her five-year tenure, her government conducted the Marian persecutions, which resulted in the execution of over 280 individuals convicted of religious dissent, a period often referred to as the era of her nickname, “Bloody Mary.”

Mary was the sole surviving legitimate child of King Henry VIII and his first wife, Catherine of Aragon. Following her parents’ marriage annulment in 1533, she was declared illegitimate and excluded from succession; however, she was later reinstated in the line of succession by the Third Succession Act of 1543. Her younger half-brother, Edward VI, succeeded Henry VIII in 1547 at the age of nine. In 1553, with Edward approaching the end of his life, he sought to exclude Mary from the succession due to her Catholic faith and her intention to reverse Protestant reforms. Consequently, a group of leading political figures proclaimed Lady Jane Grey as queen. Mary swiftly responded by raising forces in East Anglia and successfully deposed Lady Jane Grey to become queen.

Mary I (February 18, 1516 – November 17, 1558) was the sole surviving child of King Henry VIII and his first wife, Catherine of Aragon, reign was marked by efforts to restore the Roman Catholic Church and reverse the religious reforms initiated during her father, King Henry VIII’s, reign. Although her endeavors to recover church lands confiscated in previous reigns faced considerable opposition from Parliament, her reign was notably characterized by the persecution of religious dissenters, resulting in over 280 individuals being executed by burning at the stake during her tenure—an episode often referred to historically as the Marian persecutions.

Mary was initially declared illegitimate and excluded from succession following the annulment of her parents’ marriage in 1533. She was later reinstated in the line of succession through the Third Succession Act of 1543. Her younger half-brother, Edward VI, ascended to the throne in 1547 at nine years old. In 1553, upon Edward’s declining health, he attempted to exclude Mary from the succession due to the expectation that she would restore Catholic practices. Following Edward’s death, political leadership initially proclaimed Lady Jane Gray as queen; however, Mary quickly mobilized support in East Anglia and successfully deposed Lady Jane, establishing herself as queen.

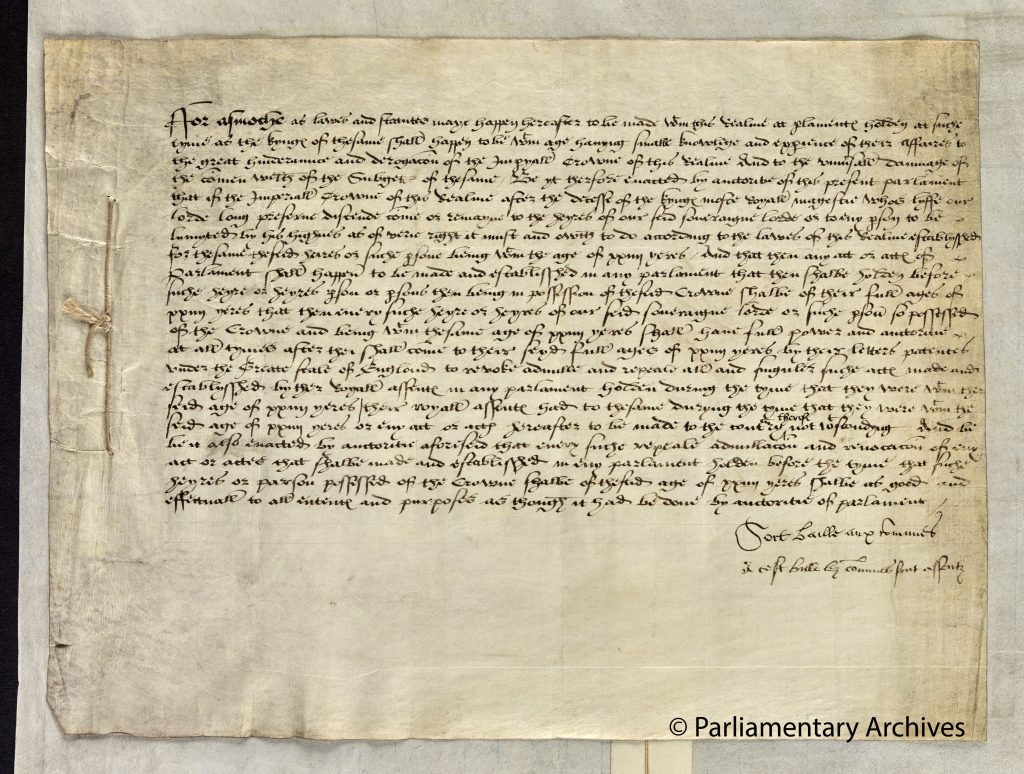

The First Act of Succession was enacted on 23rd March 1534 by King Henry VIII.

The legislation declared that his daughter with Catherine of Aragon was legally illegitimate, thereby reclassifying Mary from Princess to Lady. This act also established that any children Henry had with his new wife, Anne Boleyn, would be considered the legitimate heirs to the throne, with male offspring taking precedence over females. Anne’s first child, Elizabeth, became the heir apparent, unless Henry’s primary desire for a male heir was fulfilled.

Additionally, the Act mandated that all subjects swear an oath recognising Anne as Henry’s lawful wife and acknowledging her children as the authentic heirs. It also required allegiance to Henry as the Supreme Head of the Church of England. Failure to comply with this oath was deemed treasonous under the Treasons Act. Notably, individuals such as Sir Thomas More and Bishop John Fisher refused to take the oath and subsequently faced execution for treason.

Mary I (18 February 1516 – 17 November 1558). Mary was the sole surviving legitimate child of King Henry VIII and his first wife, Catherine of Aragon. However, following her parents’ marriage annulment in 1533, she was declared illegitimate and excluded from the line of succession by the First Act of Succession Act 1553. Henry used this act to have Anne Boleyn, his second wife and their children heirs to the throne. During her reign, she actively sought to restore the Roman Catholic Church and reverse the religious reforms initiated during her father, King Henry VIII’s, rule. Her efforts to regain church property confiscated in previous reigns faced significant opposition from Parliament.

Executions:

The primary method used during this period to suppress religious dissent involved the burning of individuals deemed heretics at the stake.

Nickname:

The extensive number of executions contributed to Queen Mary I earning the moniker “Bloody Mary.”

Notable Groups:

Among those affected were the Oxford Martyrs—Hugh Latimer, Nicholas Ridley, and Archbishop Thomas Cranmer—and the Lewes Martyrs, a group of 17 Protestants who were burned in Sussex.

Context:

These persecutions were a direct response to the English Reformation and the Protestant reforms established by Queen Mary’s predecessors.

Legacy:

The events and the memory of those who were executed as martyrs have been documented in texts such as John Foxe’s Book of Martyrs and continue to be recognized as a significant part of English historical heritage.