THE CHRISTIAN CHURCH IN THESE

ISLANDS BEFORE THE COMING

OF AUGUSTINE.

Three Lectures delivered at St. Paul’s in January 1894

BY THE

REV. G. F. BROWNE, B.D., D.C.L.,

CANON OF ST. PAUL’S,

AND FORMERLY DISNEY PROFESSOR OF ARCHÆOLOGY IN THE

UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE.

PUBLISHED UNDER THE DIRECTION OF THE TRACT COMMITTEE.

LONDON:

SOCIETY FOR PROMOTING CHRISTIAN KNOWLEDGE,

NORTHUMBERLAND AVENUE, W.C.; 43, QUEEN VICTORIA STREET, E.C.

NEW YORK: E. & J. B. YOUNG & CO.

1894.

We are approaching an anniversary of the highest interest to all English

people: to English Churchmen first, for it is the thirteen-hundredth

anniversary of the planting of the Church of England; but also to all who

are proud of English civilisation, for the planting of a Christian Church

is the surest means of civilisation, and English civilisation owes

everything to the English Church. In 1897 those who are still here will

celebrate the thirteen-hundredth anniversary of the conversion of

Ethelbert, king of the Kentish people, by Augustine and the band of

missionaries sent by our great benefactor Gregory, the sixty-fourth bishop

of Rome. I am sorry that the limitation of my present subject prevents me

from enlarging upon the merits of that great man, and upon our debt to

him. Englishmen must always remember that it was Gregory

who gave to the

Italian Mission whatever force it had; it was Gregory who gave it courage,

when the dangers of a journey through France were sufficient to keep it

for months shivering with fear under the shadow of the Alps; it was

Gregory who gave it such measure of wisdom and common sense as it had,

qualities which its leader sadly lacked. Coming nearer to the present

year, there will be in 1896 the final departure of Augustine from Rome to

commemorate, on July 23, and his arrival here in the late autumn. In 1895

there will be to commemorate the first departure from Rome of Augustine

and his Mission, by way of Lérins and Marseilles to Aix, and the return of

Augustine to Rome, when his companions, in fear of the dangers of the way,

refused to go further. An ill-omened beginning, prophetic and prolific of

like results. The history of the Italian Mission is a history of failure

to face danger. Mellitus fled from London, and got himself safe to Gaul;

Justus fled from Rochester, and got himself safe to Gaul; Laurentius was

packed up to fly from Canterbury and follow them[1]; Paulinus fled from

York. In 1894 we have, as I believe, to commemorate the final abandonment

of earlier and independent plans for the conversion of the English in

Kent, from which abandonment the Mission of Augustine came to be.

It is a very interesting fact that just when we are preparing to

commemorate the thirteen-hundredth anniversary of the introduction of

Christianity into England, and are drawing special attention to the fact

that Christianity had existed in this island, among the Britons, for at

least four hundred years before its introduction to the English, our

neighbours in France are similarly engaged. They are preparing to

celebrate in 1896 the fourteen-hundredth anniversary of “the introduction

of Christianity into France,” as the newspapers put it. This means that

in 496, Clovis, king of the Franks, became a Christian; as, in 597,

Ethelbert, king of the Kentish-men, became a Christian[2]. As we have to

keep very clear in our minds the distinction between the introduction of

Christianity among the English, from whom the country is called England,

and its introduction long before into Britain; so our continental

neighbours have to keep very clear the difference between the introduction

of Christianity among the Franks, from whom the country is called France,

and its introduction long before into Gaul. The Archbishop of Rheims,

whose predecessor Remigius baptized Clovis in 496, is arranging a solemn

celebration of their great anniversary; and the Pope has accorded a six

months’ jubilee in honour of the occasion. No doubt the Archbishop of

Canterbury, whose predecessor Augustine baptized Ethelbert, will in like

manner make arrangements for a solemn celebration of our great

anniversary. It would be an interesting and fitting thing, to hold a

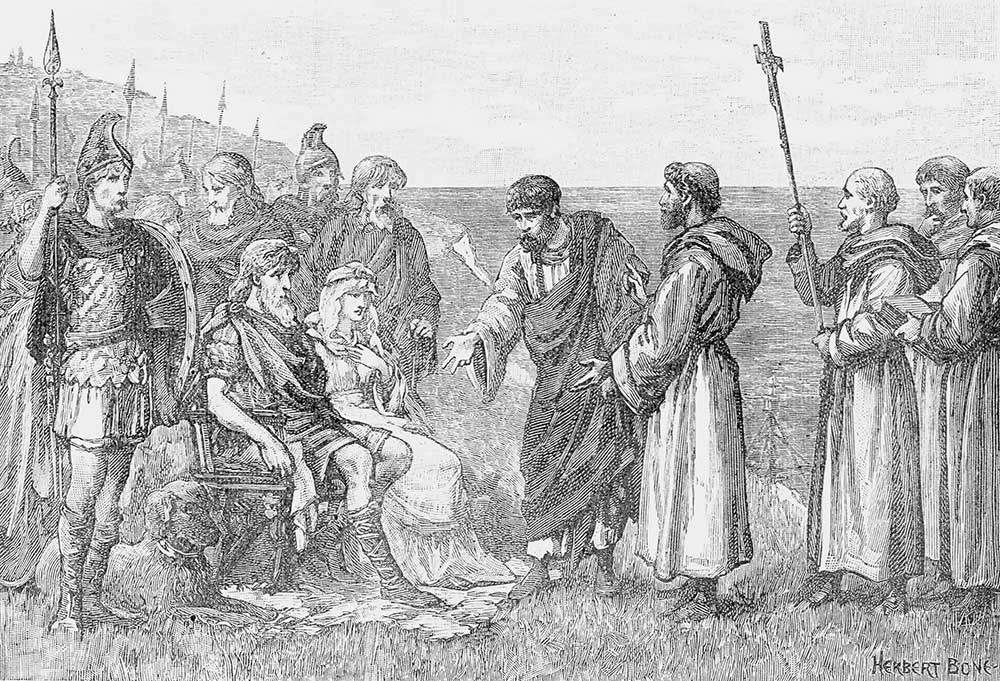

thanksgiving service within the walls of Richborough, which is generally

accepted as the scene of Augustine’s first interview with King Ethelbert,

and has now been secured and put into the hands of trustees[3]. The two

commemorations, at Rheims and at Canterbury, are linked together in a

special way by the fact that Clotilde, the Christian wife of Clovis, was

the great-grandmother of Bertha, the Christian wife of Ethelbert.

In the year 594, two years before the arrival of Augustine, there was, and

I believe had long been, a Christian queen in pagan Kent; there was, and I

believe had long been, a Christian bishop in pagan Canterbury, sent there

to minister to the Christian queen. An excellent opening this for the

conversion of the king and people, an opening intentionally created by

those who made the marriage on the queen’s side. But, however hopeful the

opening, the immediate result was disappointing. If more of missionary

help had been sent from Gaul, from whence this bishop came, the conversion

of the king and people might have come in the natural way, by an inflow of

Christianity from the neighbouring country. But such help, though

pressingly asked for, was not given; and as I read such signs as there

are, this year 594, of which we now inaugurate the thirteen-hundredth

anniversary, was the year in which it came home to those chiefly concerned

that the conversion was not to be effected by the means adopted. Beyond

some very limited area of Christianity, only the queen and some few of her

people, and the religious services maintained for them, the bishop’s work

was to be barren. The limited work which he did was that for which

ostensibly he had come; but I think we are meant to understand that his

Christian ambition was larger than this, his Christian hope higher. I

shall make no apology for dwelling a little upon the circumstances of this

Christian work, immediately before the coming of Augustine. It may seem a

little discursive; but it forms, I think, a convenient introduction to our

general subject.

Who Bishop Luidhard was, is a difficult question. That he came from Gaul

is certain, but his name is clearly Teutonic; whence, perhaps, his

acceptability as a visitor to the English. He has been described as Bishop

of Soissons; but the lists of bishops there make no mention of him, nor do

the learned authors and compilers of Gallia Christiana. This assignment

of Luidhard to the bishopric of Soissons may perhaps be explained by an

interesting story.

The Bishop of Soissons, a full generation earlier than the time of which

we are speaking, was Bandaridus. He was charged before King Clotaire, that

one of the four sons of the first Clovis who succeeded to the kingdom

called “of Soissons,” with many offences of many kinds; and he was

banished. He crossed over to England–for so Britain is described in the

old account–and there lived in a monastery for seven years, performing

the humble functions of a kitchen-gardener. Whether the story is

sufficiently historical to enable us to claim the continuance of Christian

monasteries of the British among the barbarian Saxons so late as 540, I am

not clear. There was a little Irish monastery at Bosham, among the pagan

South-Saxons, a hundred and forty years later. It is easy, I think, to

overrate the hostility of the early English to Christianity. Penda of

Mercia has the character of being murderously hostile; but it was land,

not creed, that he cared for. He was quite broad and undenominational in

his slaughters.

There is one very interesting fact, which deserves to be noted in

connection with this mysterious Gallican bishop. The Italian Mission paid

very special honour to his memory and his remains. There is in the first

volume of Dugdale’s Monasticon[5] a copy of an ancient drawing of St.

Augustine’s, Canterbury. This is not, of course, the Cathedral Church,

which was an old church of the British times restored by Augustine and

dedicated to the Saviour; “Christ Church” it still remains. St.

Augustine’s was the church and monastery begun in Augustine’s lifetime,

and dedicated soon after his death to St. Peter and St. Paul, as Bede (i.

33) and various documents tell us precisely. This fact, that the church

was dedicated to St. Peter and St. Paul, was represented last June, when

“the renewal of the dedication of England to St. Mary and St. Peter” took

place[6], by the statement that “the first great abbey church of

Canterbury was dedicated to St. Peter.” In the preparatory pastoral,

signed by Cardinal Vaughan and fourteen other Roman Catholic Bishops,

dated May 20, 1893, the statement took this form[7]:–“The second

monastery of Canterbury was dedicated to St. Peter himself.” Not only is

that not so, but I cannot find evidence that Augustine dedicated any

church anywhere “to St. Peter himself.” Of the two Apostles, St. Peter and

St. Paul, who were united in the earliest of all Saints’ days, and still

are so united in the Calendar of the Roman Church, though we have given to

them two separate days, of the two, if we must choose one of them, St.

Paul, not St. Peter, was made by Augustine the Apostle of England. To St.

Paul was dedicated the first church in England dedicated to either of the

two “himself,” that is, alone; and that, too, this church, the first and

cathedral church of the greater of the two places assigned by Gregory as

the two Metropolitical sees of England, London and York.

THE PAPAL AGGRESSION! CREATION OF

THE ROMAN CATHOLIC HIERARCHY

IN ENGLAND, 1850

APPROVED!

Major professor ^

J?, / / / ?

Minor Professor

ItfCp&ctor of the Departflfejalf of History

Dean”of the Graduate School

THE PAPAL AGGRESSION 8 CREATION OP

THE SOMAN CATHOLIC HIERARCHY

IN ENGLAND, 1850

THESIS

Presented to the Graduate Council of the

North Texas State University in Partial

Fulfillment of the Requirements

For she Degree of

MASTER OF ARTS

By

Denis George Paz, B. A,

Denton, Texas

January, 1969

PREFACE

Pope Plus IX, on September 29» 1850, published the

letters apostolic Universalis Sccleslae. creating a terri-

torial hierarchy for English Roman Catholics. For the

first time since 1559» bishops obedient to Rome ruled over

dioceses styled after English place names rather than over

districts named for points of the compass# and bore titles

derived from their sees rather than from extinct Levantine

cities« The decree meant, moreover, that6 in the Vati-

can ks opinionc England had ceased to be a missionary area

and was ready to take its place as a full member of the

Roman Catholic communion.

When news of the hierarchy reached London in the mid-

dle of October, Englishmen protested against it with

unexpected zeal. Irate protestants held public meetings

to condemn the new prelates» newspapers cried for penal

legislation* and the prime minister, hoping to strengthen

his position, issued a public letter in which he charac-

terized the letters apostolic as an “insolent and

insidious”1 attack on the queen’s prerogative to appoint

bishops„ In 1851» Parliament, despite the determined op-

position of a few Catholic and Peellte members, enacted

the Ecclesiastical Titles Act, which imposed a ilOO fine

on any bishop who used an unauthorized territorial title,

ill

and permitted oommon informers to sue a prelate alleged to

have violated the act. But no bishop ever was found

guilty under this law, and it was repealed twenty years

later.